PEARLS OF WISDOM

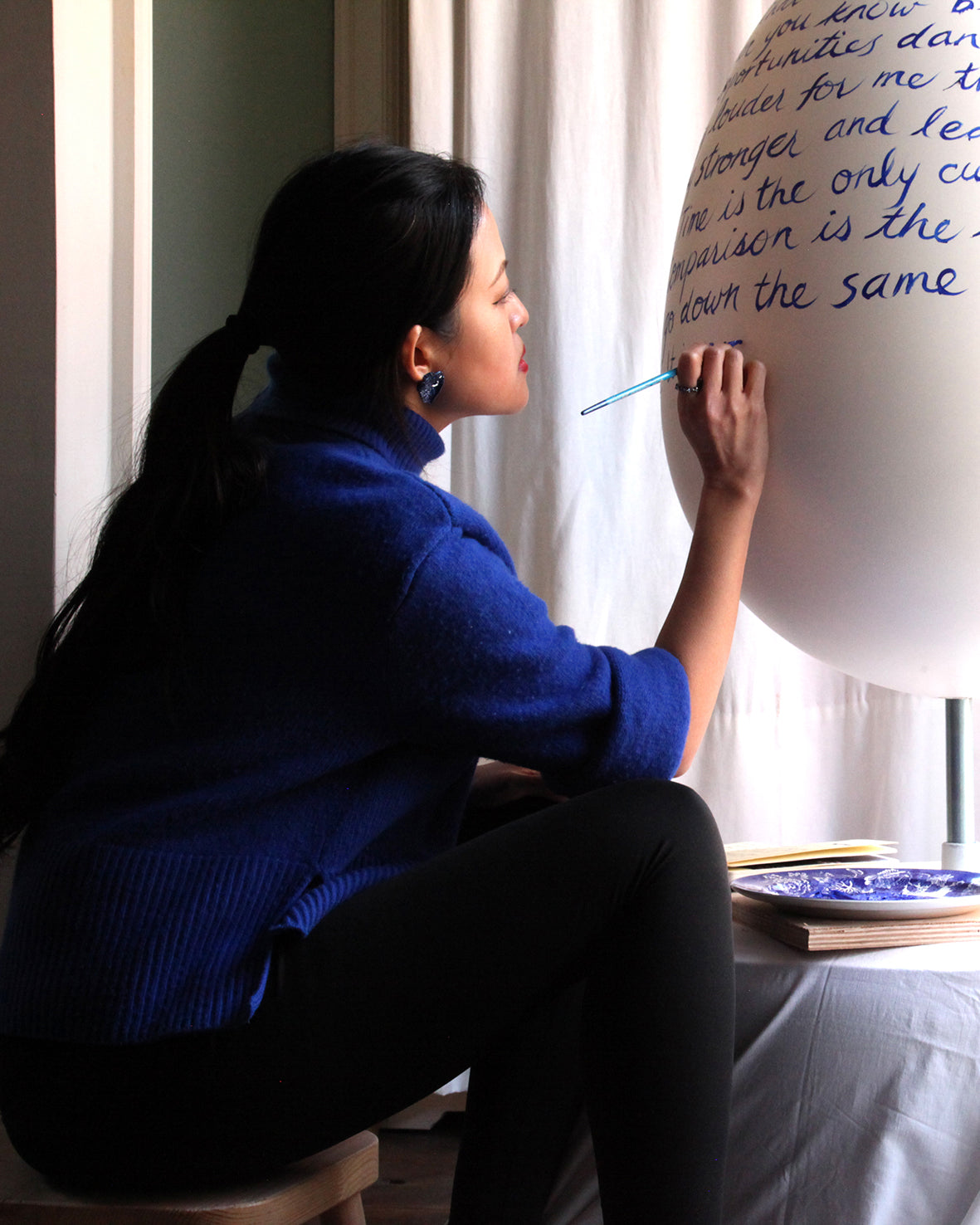

By collaborating with an eco-sensitive pearl supplier in French Polynesia, Anabela Chan's sculptural pieces have been designed in natural harmony. By KIM PARKER

Pearls have always had a special significance for Anabela Chan. "My grandmother wore her string of pearls religiously, even if she was just visiting the market. I always admired that," says the London-based jeweller, who recalls growing up in Hong Kong surrounded by elegant, pearl-wearing relatives. "For every Chinese auntie it was pearls over diamonds any day. There was something so romantic about it." When Chan was a teenager, she attempted to cast her dream pearl piece for a school assignment, aided by the renowned designer Andrew Grima: a yellow-gold pocket square, encasing a single grey Tahitian pearl. Sadly, it never materialised. "The pocket square was too fragile to hold its shape, and the ideal pearl never came my way," she says.

Some 20 years later, Chan's latest undertaking promises to fulfil her childhood obsession with the nacreous gems. Now known for her nature-inspired jewels wrought from recycled metals and carefully considered gemstones, the designer is working on her first (as yet unnamed) collection dedicated to rare and colourful pearls. "I've wanted to do this for years, but could never find the right supplier that harvested spectacular pearls in a way that aligned with my values,"reveals Chan. Then, during the 2020 lockdown, she was quoted in an article about ethical jewellery alongside the gemologist Laurent Cartier, who lauded the efforts of a boutique, family-run sustainable pearl farm called Kamoka Pearls, based in French Polynesia. "I researched Kamoka and their work to conserve the waters around the Ahe atoll, and I knew I'd found my perfect collaborators," says Chan.

Located 300 miles northeast of Tahiti, Kamoka was founded in the early 1990s by the Humbert family, who have pioneered some of the strictest levels of sustainable pearl farming over the ensuing decades. The high-powered hoses used to clean oyster shells by commercial operations (which alter the pH of seawater and disrupt the local ecosystem) have been replaced with native fish species, which pick the oysters clean. As a result, Kamoka's native marine population, including previously endangered species, is now thriving, bolstered by a protected breeding reserve. What's more, by only using oyster mother-of-pearl shell nuclei in its cultured pearls (rather than mussel shell nuclei), Kamaka has created gems of unparalleled hue and lustre. "They're called 'unicorn' pearls, because they are so fantastically rare and beautiful," says Chan. "I'd never bought gemstones without holding them in my hand before, but I spent hours on Zoom with the Humberts, choosing the perfect ones. It was heavenly."

Chan's unicorn pearls will be the centrepiece of a 20-piece collection of earrings, pins and rings set to launch later this year. Inspired by the plants in Chan's own garden, recycled aluminium and yellow gold have been fashioned into delicately curling fern leaves, or sleek blades of grass, embellished with gleaming pearl" dewdrops", lab-created diamonds, sapphires and garnets. "I loved the idea of elevating something humble like a leaf into a sculptural piece of art; in the same way that an oyster can transform a grain of sand into an amazing pearl," says Chan. And just as she envisioned her gold pocket square as a unisex accessory, these pieces are also designed to be worn by anyone. The pocket square itself may even stage a comeback. "I've finally found the perfect grey pearl which could be set inside it," enthuses Chan. "Watch this space."

OUR STORIES

Fruit Gems™ featured in Financial Times

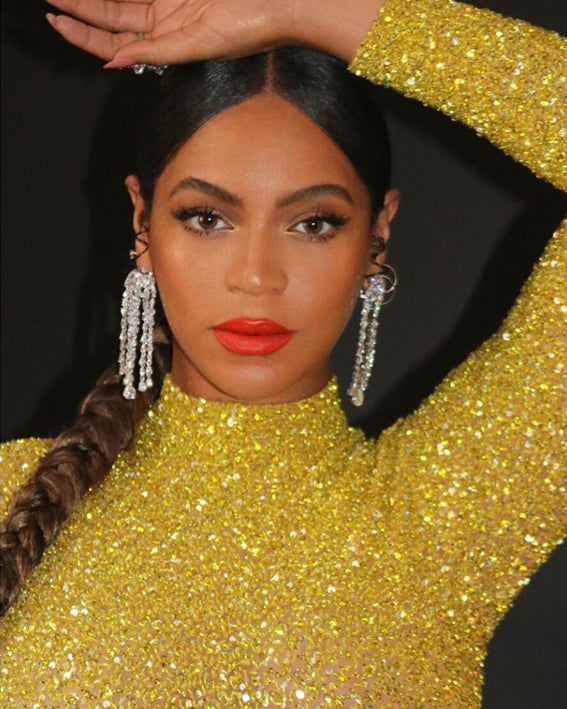

Mariah Carey wears Anabela Chan Joaillerie for her new album cover

Taylor Swift wears the Diamond Cushion Wing Studs

- Choosing a selection results in a full page refresh.